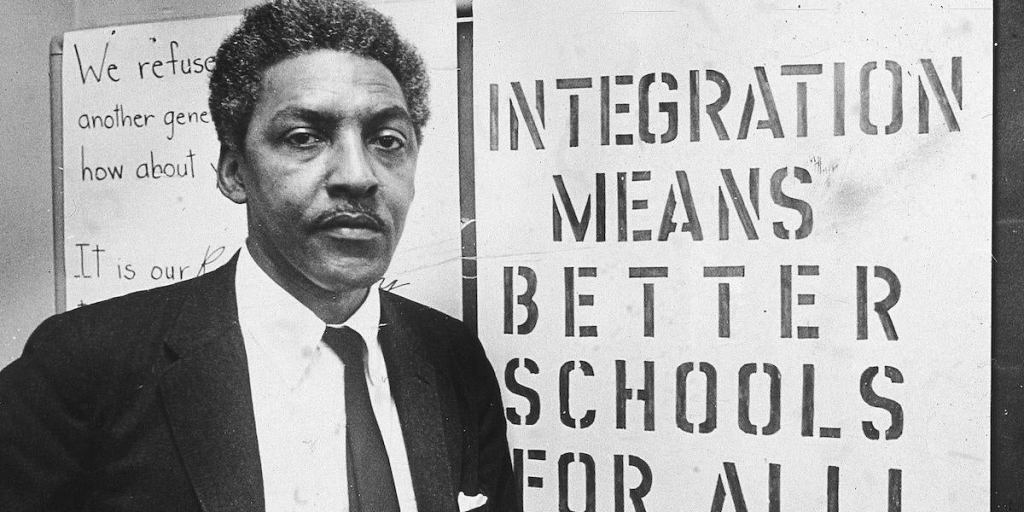

238 countries are now able to learn about a hidden Civil Rights icon thanks to a new film streaming on Netflix. Rustin tells the story of Bayard Rustin, the organizer behind the historic March on Washington of 1963. His involvement in the march was suppressed due to him being openly gay during a time when non-heterosexual sexuality was taboo. But long before the Colman Domingo-led feature, there was a documentary highlighting Rustin’s life and work by filmmaker Nancy Kates. Brother Outside: The Life Of Bayard Rustin, a groundbreaking documentary on Rustin, was released 20 years prior to the resurgence of Rustin’s name.

While the Netflix film is necessary, Kates’ documentary set the necessary groundwork, and should not go unrecognized. PopCulture spoke with Kates about her dedication to showcasing Rustin’s work, and how the new film, despite her not being involved, is a needed extension.

Videos by PopCulture.com

PC: When did your work and your research on Bayard Rustin actually begin, and what was your initial attraction to him as a Civil Rights leader?

NK: Jervis Anderson, who was a reporter or a writer for The New Yorker, published a book called, I think it was called Bayard Rustin: Troubles I’ve Seen, or maybe it’s the other way around, but Troubles I’ve Seen is definitely part of the title. And I read the review, the New York Times book review, and I had vaguely heard of Rustin and I had colleagues and friends who had worked on Eyes on the Prize, the landmark Civil Rights television series that was made in Boston out of a company called Blackside. But I read this review, which was basically a biography of his life, and I thought, “Wow, look what this man did with his 75 years on the planet. He was persistent and tenacious in his activism,” which he did from the age of 15 until the day he died. And I just thought, “What are the rest of us doing with our lives? I want to know about this”. And I had that idea, someone should make a film about him. And of course, if you’re a filmmaker, it’s all over right there. As soon as you have that thought, it always winds up being you. You’re the one who’s going to make a film.

But I wasn’t thinking that at first, I just thought, “Someone should make a film.” But that’s how this started. And I did more research and I was just really inspired by what he did. Part of it was that he was African-American and gay, but it was his deep commitment to social change that attracted me.

PC: Your film came out 20 years ago, so there have been a lot of advancements made for people of color and the LGBTQ+ community, but I still feel like Rustin’s work is largely unknown. Are you still surprised by that?

NK: Well, over a million people saw our film when it was broadcast, and also millions and millions of people who have never heard of him. I think that has changed a bit. I think that our film did give him greater visibility, and now that there’s this narrative film coming out, it’ll be even more so. I think people in certain communities know about him. If you were a lefty in the ’60s, you know about Rustin. More AfricanAmericans and queer people know about him than members of the general population, I would say. If you’re a Quaker, you’ve heard of him. So it’s not everyone, but I also think that intersectional figures like Rustin were ignored in the past, or in his case while he was alive. And since then, he’s come to be revered. And so, it’s been really exciting to bring the film to audiences and we continue to do that. We show it at law firms and schools and all kinds of places, churches. And it’s always a mixture, most people when I go to these events haven’t heard of him. And then they kind of were like, “Well, why haven’t I heard of him?” And I don’t want to go into some lecture about how badly we teach history in America, but I could. But I also think that the contributions of People of Color and LGBTQ people have not been taught in history in appropriate ways, and hopefully, that has changed.

PC: With this Netflix film, did you have any knowledge of this in advance of it being written?

NK: Yeah, I knew it was happening. Unfortunately, they didn’t ask me to consult on it, but I certainly knew what was happening.

PC: Would you have preferred to have been involved?

NK: I would’ve preferred to. It’s important for people to tell their own stories, and it’s clear that they studied our film very, very carefully based on looking at it. But that’s their choice. I think there’s an unfortunate trend in Hollywood that most of the time documentarians are not consulted on feature films that are on the same subject, but their films are used as kind of core texts for those narrative films. So it’s not unique to me, but they didn’t contact me.

PC: Now, with both pieces of work, with your documentary and the film, how do they work together?

NK: Well, I would even broaden it to all of my colleagues. I would tell people to go watch the documentary about Harvey Milk after they see the feature film Milk. The three-hour Oppenheimer narrative film, it’s great, but they should also go see John Ellis’s The Day After Trinity, which was made, I think in 1982. I studied with John Ellis at Stanford. It’s an extraordinary piece of work. But I think it’s also important to talk about broader things. For example, there’s also an opera about Robert Oppenheimer and the development of the atomic bomb that was, I think John Adams wrote and was at the San Francisco Opera. So, there are many ways of telling stories about historical figures, and hopefully in the future, maybe there’ll be more collaboration and acknowledgment of the work of documentarians. But I also think it’s great that the Oppenheimer film the narrative is also based on a book. So, there are many ways in which these historical narratives are presented to people.

PC: How do you hope the documentary and film will expand Rustin’s legacy?

NK: Well, I want to focus on what we did because I don’t want to speak for the narrative people. They have a different agenda too. I guess in theory, documentarians are in the entertainment business, but not really, we’re more in the education and enlightenment business. One of my goals was just to raise this visibility, which I think we have done over the last 20-odd years. Even while we were making the film, people were like, “Who was that guy?” And then suddenly I was like, “Oh.”, then people had heard about him. I always wanted to make sure that people knew that someone who was a Person of Color and queer had made such an enormous contribution to American history.

I imagine that the people making this new film have a similar agenda. There is no reason why figures like Rustin or Ella Baker, who was his friend, another important Civil Rights figure, all sorts of other people aren’t household names in every part of America. But unfortunately, I think part of that has to do with racism homophobia, and sexism in the case of Ella Baker. I think we’ve made a lot of progress, and there’s still a lot of work to be done.

PC: What similarities do you see as far as the plight of LGBTQ+ People of Color now and when Rustin was leading and organizing the march on Washington and was kind of not given the credit, probably due to his sexuality?

NK: I think he was seen as a political liability by some of King’s allies, particularly Adam Clayton Powell, who was the congressman from Harlem, who kind of threw his sexuality in the face of King, and Powell was throwing his weight around. I think that it was less possible to be fully out in 1963 than it is today, clearly. I think that there’s a certain amount of homophobia in the African-American community that was probably more in the past than there is now.

Unfortunately, there’s racism in the gay community. As an ally hopefully, I’m Jewish, I’m not African-American, but I hope that more and more and more Americans are working for racial justice. It feels like a very ugly time about race and sexuality in America. But maybe these things just go in cycles and some of the horrible stuff that maybe was said behind closed doors got a little more overt in the last 10 years. It’s hard to say. I mean, things keep changing, but the fact that trans youth can’t get medical treatment now in a number of states is kind of hard to fathom. There’s so much more acceptance of all kinds of LGBTQ people in communities than there ever was. The fact that we have a vice president who’s both African-American and Asian-American is extraordinary. But we still have a long way to go.